Guide to Political Slang in China

Navigating Chinese political discourse requires understanding unique terminology, reflecting historical shifts and the Communist Party’s influence. This guide

explores key phrases,

modern buzzwords, and online slang, revealing layers of meaning within China’s evolving political landscape.

Chinese political discourse is a complex tapestry woven with historical context, ideological underpinnings, and nuanced linguistic expressions. Understanding this landscape necessitates recognizing that language isn’t merely a tool for communication, but a powerful instrument of control and persuasion wielded by the state. The Communist Party’s influence permeates all levels of communication, shaping narratives and defining acceptable boundaries of expression.

Political terminology in China often carries layers of meaning, extending beyond literal translations. Terms can evolve rapidly, acquiring new connotations based on current events and policy shifts. The recent session of China’s top political advisory body, as reported by Xinhua, highlights the ongoing refinement of political messaging. Furthermore, the upcoming Communist Party meeting in late October signals potential shifts in the country’s five-year plan, impacting future vocabulary.

Analyzing this discourse requires sensitivity to censorship and the prevalence of euphemisms, alongside an awareness of the growing economic imbalances and the Party’s response through initiatives like “Common Prosperity.”

Historical Context of Political Terminology

The evolution of Chinese political terminology is deeply rooted in the nation’s tumultuous 20th and 21st-century history. The language of the Cultural Revolution, with its emphasis on class struggle and ideological purity, left a lasting imprint, even as official rhetoric shifted. Maoist-era slogans, though less frequently used overtly, continue to resonate in subtle ways.

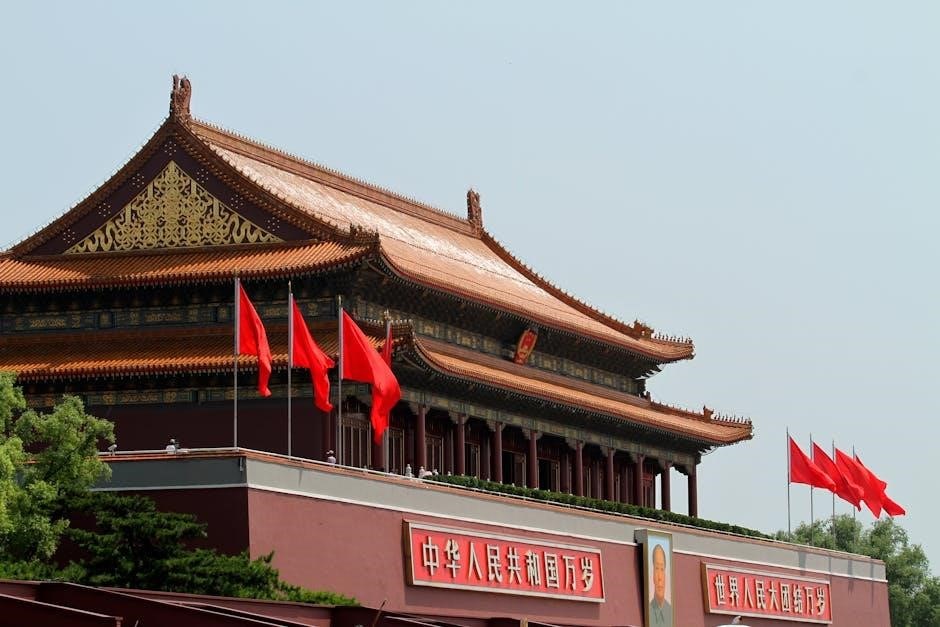

Post-Deng Xiaoping reforms introduced market-oriented language, yet this coexisted with continued emphasis on socialist principles. The Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 led to increased sensitivity around terms perceived as challenging Party authority, fostering a climate of self-censorship. More recently, Xi Jinping’s rise has ushered in a new wave of terminology, prioritizing national rejuvenation and strong leadership.

Understanding this historical trajectory is crucial for deciphering contemporary political slang. Terms aren’t static; they’re constantly reinterpreted and repurposed, reflecting China’s dynamic political landscape and the Party’s ongoing efforts to shape public opinion.

The Role of the Communist Party in Shaping Language

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) exerts significant control over political discourse, actively shaping language to reinforce its ideology and maintain social stability. This influence extends beyond formal pronouncements to encompass the subtle manipulation of terminology and the suppression of dissenting voices. The CCP utilizes propaganda and censorship to promote preferred narratives and discourage alternative interpretations.

Key concepts like “Harmonious Society” and “Common Prosperity” are not merely economic or social goals, but carefully crafted slogans designed to legitimize Party rule and foster national unity. The CCP also actively defines the boundaries of acceptable speech, labeling certain terms as “hostile” or “subversive.”

This linguistic control is further amplified by the “50 Cent Party” and online censorship mechanisms, ensuring that the Party’s message dominates the digital sphere. Understanding the CCP’s role is essential for interpreting the nuances of Chinese political slang and recognizing the underlying power dynamics at play.

Key Terms & Phrases

Essential for deciphering Chinese political communication, these terms – “Chinese Virus,” “Foreign Hostile Forces,” and “No Haste, Be Patient” – reveal core ideological viewpoints and strategies.

“Chinese Virus” ( ౼ Zhōngguó Bìngdú) ౼ Origins and Usage

The term “Chinese Virus” (Zhōngguó Bìngdú) gained prominence during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily originating outside of China and quickly becoming a point of contention. Initially used to describe the virus’s geographic origin, it was often employed, particularly by figures like former US President Trump, in a manner perceived as nationalistic and accusatory towards China.

Within China, the phrase is largely viewed as a derogatory and politically motivated label, intended to stigmatize the country and deflect blame for the pandemic’s global spread. Chinese state media and officials strongly condemned its usage, framing it as racist and harmful to international cooperation. The term became a symbol of strained Sino-Western relations during the pandemic, highlighting existing geopolitical tensions.

Its usage sparked considerable debate regarding the ethics of associating diseases with specific nationalities or ethnicities. While some argued it was a simple descriptor of origin, others countered that it fueled xenophobia and anti-Chinese sentiment. The phrase remains a sensitive topic, representing a period of global crisis and heightened political rhetoric.

“Foreign Hostile Forces” ( ⎻ Wàiguó Díduì Shìlì) ⎻ Defining the “Other”

“Foreign Hostile Forces” (Wàiguó Díduì Shìlì) is a broad and often vaguely defined term used extensively in Chinese state media and official discourse. It serves as a catch-all phrase to encompass any external entities perceived as challenging the authority of the Communist Party or undermining China’s political stability and national interests. This includes governments, organizations, and individuals critical of China’s policies.

The concept is deeply rooted in the Party’s narrative of safeguarding national sovereignty and resisting external interference. It’s frequently invoked to justify strict censorship, crackdowns on dissent, and heightened security measures. Defining the “Other” through this lens allows the Party to consolidate power and rally public support against perceived threats.

Critically, the term lacks precise definition, enabling its application to a wide range of actors and activities, from legitimate journalistic reporting to peaceful advocacy for human rights. This ambiguity contributes to a climate of suspicion and restricts open dialogue about sensitive political issues within China.

“No Haste, Be Patient” ( ⎻ Bù jí yú qiú chéng) ౼ Political Strategy & Patience

“No Haste, Be Patient” (Bù jí yú qiú chéng) encapsulates a core tenet of the Chinese Communist Party’s long-term strategic thinking. This proverb, frequently cited by officials, emphasizes a deliberate, incremental approach to achieving political and economic goals, rejecting the pursuit of rapid or revolutionary change. It reflects a preference for stability and controlled development over potentially disruptive reforms.

The phrase signals a willingness to endure prolonged periods of effort and setbacks, trusting that consistent, methodical work will ultimately yield desired results. It’s often used to justify slow progress on politically sensitive issues, such as democratic reforms or addressing human rights concerns. Patience is presented as a virtue, demonstrating strength and resolve.

However, critics argue that “No Haste, Be Patient” can also serve as a justification for inaction and a means of deflecting pressure for meaningful change, prioritizing the Party’s continued rule above all else.

“Non-Party Intellectuals” ( ⎻ Fēi Dǎng Zhīshì Fènzǐ) ⎻ A Complex Social Group

“Non-Party Intellectuals” (Fēi Dǎng Zhīshì Fènzǐ) refers to individuals with higher education and professional expertise who are not members of the Chinese Communist Party. This group occupies a unique and often precarious position within Chinese society, valued for their skills but viewed with caution due to their independence from Party control.

Historically, these intellectuals have played a significant role in shaping public discourse and challenging established norms. However, they’ve also faced periods of political repression, particularly during times of ideological tightening. The Party seeks to co-opt and guide their thinking, offering limited avenues for independent expression.

Today, “Non-Party Intellectuals” navigate a complex landscape of opportunities and constraints, often self-censoring to avoid political repercussions. Their contributions are sought in specific areas, but their overall influence remains carefully managed by the CCP.

Modern Political Buzzwords

Contemporary Chinese politics features trending terms like “Common Prosperity” and “Wolf Warrior Diplomacy,” reflecting current ideologies and nationalistic ambitions, shaping public perception and policy direction.

“Common Prosperity” ( ౼ Gòngtóng Fùyù) ౼ Xi Jinping’s Economic Vision

“Common Prosperity” (Gòngtóng Fùyù) represents a core tenet of Xi Jinping’s economic philosophy, signaling a shift from prioritizing rapid economic growth to a more equitable distribution of wealth. This isn’t a return to Maoist egalitarianism, but rather a focused effort to reduce the widening gap between rich and poor, and address perceived imbalances within Chinese society.

The concept emphasizes “reasonable common prosperity,” implying a phased approach and acknowledging existing disparities. It involves policies aimed at strengthening the middle class, increasing rural incomes, and curbing excessive wealth accumulation among individuals and corporations. The phrase gained prominence in 2021, accompanied by increased regulatory scrutiny of tech giants and calls for philanthropic contributions.

However, “Common Prosperity” also carries undertones of social control and reinforces the Communist Party’s role in guiding economic development. Critics suggest it could stifle innovation and entrepreneurship, while proponents argue it’s essential for long-term stability and sustainable growth. The term is frequently invoked in state media, solidifying its place in the current political lexicon.

“Wolf Warrior Diplomacy” ( ⎻ Zhànláng Wàijiāo) ౼ Assertive Foreign Policy

“Wolf Warrior Diplomacy” (Zhànláng Wàijiāo) describes China’s increasingly assertive and often confrontational approach to foreign relations, emerging around 2019. The term originates from the popular nationalist action film series “Wolf Warrior,” portraying patriotic Chinese soldiers defending national interests abroad.

This diplomatic style is characterized by outspoken and sometimes aggressive responses to criticism of China, particularly regarding issues like human rights, trade practices, and territorial disputes. Chinese diplomats actively engage in “pushback” on social media, fiercely defending China’s policies and challenging perceived Western biases.

While some within China view this as a necessary response to unfair treatment and a demonstration of national strength, it has drawn criticism internationally for being undiplomatic and exacerbating tensions. The shift reflects a growing confidence in China’s global standing and a willingness to challenge the existing international order. It represents a departure from Deng Xiaoping’s earlier emphasis on “peaceful rise.”

“Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” ( ౼ Zhōnghuá Mínzú Wěidà Fùxīng) ౼ Nationalistic Narrative

“Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” (Zhōnghuá Mínzú Wěidà Fùxīng) is a central tenet of Xi Jinping’s political ideology and a powerful nationalistic narrative. It frames China’s current trajectory as a restoration to its former glory, overcoming a “century of humiliation” at the hands of foreign powers.

This concept draws heavily on historical grievances and emphasizes China’s long and proud civilization. It’s used to legitimize the Communist Party’s rule, portraying it as the vehicle for achieving national renewal and restoring China to its rightful place on the world stage. The narrative fosters a sense of collective identity and purpose, rallying public support behind the Party’s goals;

The phrase appears frequently in official speeches, media reports, and educational materials, reinforcing its importance. It’s intrinsically linked to China’s ambition to become a global leader and reshape the international order, often presented as a benevolent force for progress and stability.

Online & Censorship-Related Slang

The Chinese internet features unique slang born from censorship and online activism. Terms like “river crabs” and “little pink” reveal strategies

for navigating restrictions and expressing dissent.

“Harmonious Society” ( ⎻ Héxié Shèhuì) ౼ Euphemism for Censorship

The phrase “Harmonious Society” ( ⎻ Héxié Shèhuì), popularized under Hu Jintao and continued by Xi Jinping, initially presented an appealing vision of social stability and collective well-being. However, it quickly became a widely recognized euphemism for censorship and suppression of dissent within China. The term’s frequent use often coincides with crackdowns on online speech, protests, or any expression deemed disruptive to social order by the Communist Party.

Ironically, the pursuit of “harmony” often translates to the silencing of opposing viewpoints. Online, users quickly learned to associate the term with the removal of sensitive content and the imposition of strict controls over information. It’s a subtle yet powerful example of how language is manipulated to mask authoritarian practices. The concept highlights the Party’s prioritization of maintaining control over public narrative, even at the expense of open dialogue and freedom of expression. Therefore, understanding “Harmonious Society” requires recognizing its dual meaning – the official ideal versus its practical application as a tool for censorship.

“River Crabs” ( ౼ Héxiè) ⎻ Internet Censorship & Self-Censorship

“River Crabs” ( ⎻ Héxiè) is a particularly clever piece of Chinese internet slang born from the nation’s sophisticated censorship apparatus. The term originated as a homophone for “harmonization” (héxié), a key concept promoted by the government, but quickly became a satirical reference to the blocking and deletion of online content. The image of crabs, with their pincers, symbolizes the ‘clamping down’ on sensitive information.

This slang extends beyond simply describing censorship; it also embodies the phenomenon of self-censorship. Knowing that certain keywords or topics are likely to be blocked, Chinese internet users often preemptively avoid them in their online communications. “River Crabbing” thus represents a subtle form of compliance, driven by fear of repercussions. The term’s widespread use demonstrates a collective awareness of the pervasive censorship and a wry acceptance of its limitations on free expression. It’s a potent symbol of the ongoing battle between control and communication in China’s digital sphere.

“Little Pink” ( ⎻ Xiǎo Fěnhóng) ⎻ Online Nationalist Youth

“Little Pink” ( ⎻ Xiǎo Fěnhóng) is a widely used, often derogatory, term for young, nationalistic Chinese internet users. The “pink” refers to the color associated with a relatively harmless, early form of online activism, but the term now signifies a more assertive and often aggressive online presence. These individuals are characterized by their fervent support for the Chinese Communist Party and their willingness to defend China’s interests – as they perceive them – in online spaces.

They frequently engage in online debates, often targeting perceived critics of China, and are known for coordinated campaigns to amplify pro-government narratives. While some see them as genuine patriots, others view them as a form of online astroturfing, potentially influenced or encouraged by state actors. The “Little Pink” phenomenon highlights the growing influence of nationalism among China’s youth and the government’s ability to mobilize online support, shaping public opinion and countering dissenting voices.

“50 Cent Party” ( ౼ Wǔmáo Dǎng) ౼ Paid Online Commentators

The “50 Cent Party” ( ⎻ Wǔmáo Dǎng) refers to individuals allegedly employed by the Chinese government to post pro-government comments online and shape public opinion. The name originates from the claim that commentators were initially paid 50 Chinese cents (approximately US$0.07) per post. While the actual payment structure is debated, the term has become synonymous with state-sponsored online propaganda and censorship.

These commentators are believed to operate on various online platforms, including social media, forums, and news websites, aiming to steer discussions in favor of the Communist Party and deflect criticism. Their activities include praising government policies, attacking dissidents, and spreading disinformation. The existence of the “50 Cent Party” raises concerns about the authenticity of online discourse in China and the extent to which public opinion is manipulated by state actors, impacting the free flow of information.

Evolving Political Vocabulary

China’s political language constantly adapts, influenced by technology like AI and shifting priorities. This dynamic evolution impacts manipulation tactics and shapes online narratives significantly.

The Impact of AI on Political Language Manipulation

Artificial intelligence is increasingly utilized in China to refine and amplify political messaging, presenting both opportunities and challenges. Reports indicate suspected Chinese government operatives have explored ChatGPT’s capabilities to develop tools for large-scale surveillance and social media monitoring. This includes crafting proposals for systems designed to scan online accounts, potentially identifying and influencing public opinion.

The use of AI extends to generating persuasive content and automating the dissemination of propaganda. This raises concerns about the authenticity of online discourse and the potential for manipulation. AI can assist in tailoring narratives to specific audiences, exploiting existing biases, and creating a distorted perception of reality. Furthermore, AI-powered tools can be employed to detect and suppress dissenting voices, reinforcing censorship and control over information flow.

The sophistication of these techniques necessitates a critical approach to consuming information originating from or about China, recognizing the potential for AI-driven manipulation and the blurring lines between genuine expression and orchestrated campaigns.